Staying on the right side of global property's challenges

Global property managers have had to keep risk management top of mind over the last few years. I spoke to Catalyst's Ryan Cloete about the firm's approach to analysing assets.

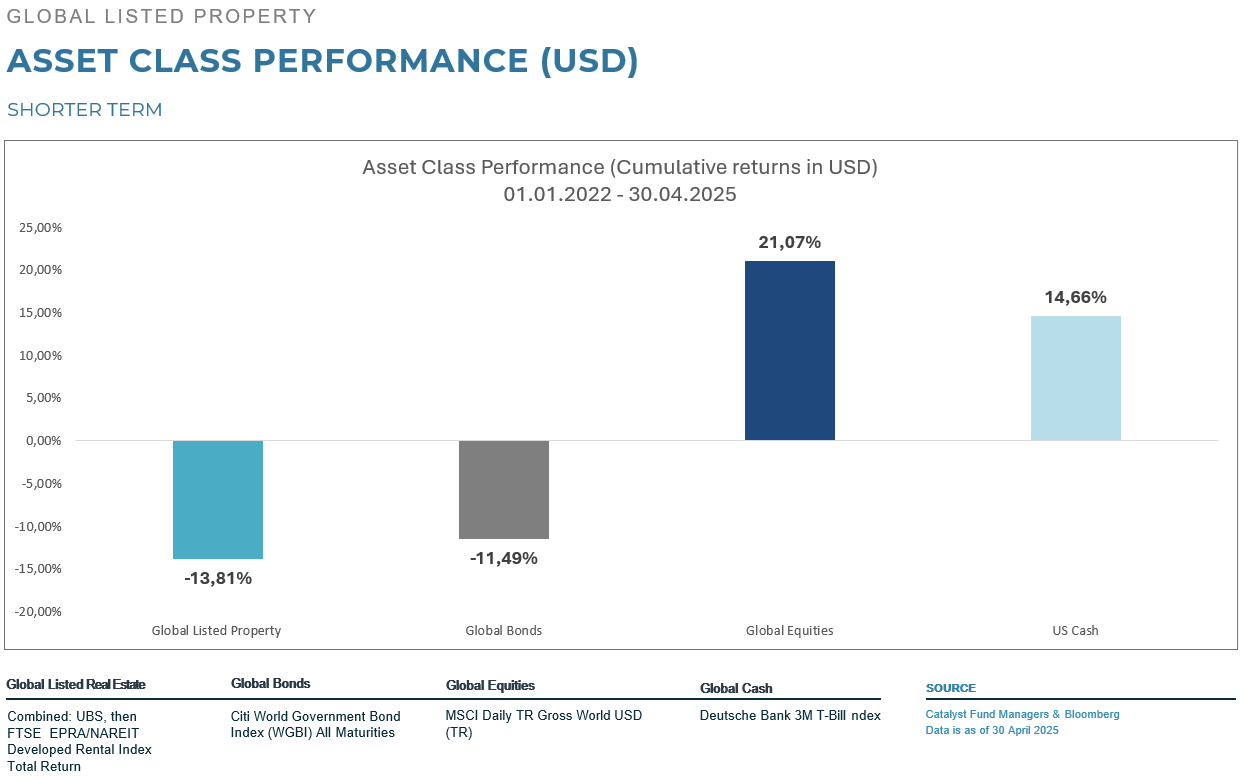

Global real estate has been a tough place to invest for the past three years. Between the start of 2022 and the end of April this year, the asset class has lost nearly 14%.

Concerns about economic growth and uncertainty about the path of interest rates have not made things any easier in 2025. And while co-portfolio manager of the Catalyst Global Real Estate UCITS Fund, Ryan Cloete, argues that fundamentals in the sector are good, there is high visibility to earnings growth due to secular demand drivers in many sectors, and valuations look increasingly attractive, risk management remains critical.

“Where we spend most of our time is in trying to understand company fundamentals,” Cloete says. “That is what allows us to model an earnings growth profile and dividend stream, and attach risk to them. We spend a lot of time building up a unique hurdle rate for every stock in our investible universe.

“We have scorecards looking at things like each stock’s balance sheet, levels of debt, sources of debt and duration of debt. For companies that don’t score well on those factors, we require a higher hurdle rate. We also look at management and their track record of capital allocation. Again, we raise the hurdle rate for companies that don’t score well there.”

Avoiding excessive risk

This approach helps the firm to avoid high risk assets, as illustrated by its approach to Intu Properties prior to that company entering administration in 2020.

“Before things went belly-up, a lot of people were saying that Intu is trading on such a high dividend yield that even if we don’t get earnings growth we will still see a great return,” Cloete recalls. “But it was uninvestible for us because we saw risks to its balance sheet and that the company might have to do a capital raise.

“Our hurdle rate was so high that it kept us out of the stock, even though it might have screamed optically cheap.”

“We think about every investment as if we’re buying the underlying assets”

He believes this approach has a lot to do with the fact that Catalyst’s founders and other senior team members come from a physical real estate background. This has heavily influenced the firm’s approach.

“We think about every investment as if we’re buying the underlying assets,” Cloete says. “We think to that granular level. What are the risks to re-letting, for example, or what is the required capex. We spend a lot of time on the hurdle rate because not all cash flows are equal and come at equal risk.”

He points to the importance of capex spending in real estate as an example of a factor that needs to be deeply understood in assessing the risk to a company’s earnings.

“Something that is really underappreciated is the amount of capex that needs to be spent just to maintain a property, and different sectors have different requirements,” Cloete (pictured above) says. “With self-storage, for example, we think about 8% of net operating income needs to be reinvested. For a hotel, that number is 33%.”

This is significant because in more challenging environments, companies often scale back on their capex.

“You might not notice it immediately, but landlords have to spend that capex, or the quality of the asset is going to deteriorate,” Cloete says. “So, if you’re modelling a hotel stock and you’re only modelling capex of 5% to 10% of net operating income, you’re going to get a really different outcome to us when we’re modelling something much higher.”

Assessing earnings

Catalyst is benchmark cognisant in building the portfolio, but Cloete and his team make risk assessments at a sector level as well. For example, the fund has been underweight the office sector for more than half a decade.

“Even pre-Covid, we held the view that the amount of capex needed to maintain an office building and keep it prime is under-appreciated by the market,” Cloete says. “In our modelling, we’ve always handicapped the office sector more than many of our peers and struggled to find value.

“On top of that, since Covid there’s been a material change to a hybrid work environment, which has resulted in less demand. What we’ve seen is that there’s a huge bifurcation between the prime assets that everyone is chasing, and lower quality assets where no one wants to be.

“The value of lower quality assets could become quite low.”

“That said, we still need to go into individual company portfolios to see what kind of assets they have. Landlords with higher quality buildings will have pricing power, while the value of lower quality assets could become quite low.”

Conversely, single-family housing in the US is an area where Catalyst is overweight. The firm sees it as a sub-sector benefitting from secular trends that will likely remain positive even in a weaker economic environment.

“The largest living demographic in the US is millennials. And they are at the age when traditionally people start to move out of apartments and into single family homes,” Cloete says.

Supply and demand visibility

“What we saw with prior generations is that many would get a mortgage to buy a home, but more millennials are choosing to rent. This is due to lending criteria from banks getting tougher, millennials carrying a lot of student debt, and the behavioural preference of having more flexibility. More recently, higher interest rates have forced even more people into renting as opposed to ownership.”

This has led to growing demand for rental housing, at the same time that supply has shrunk. This is due to many developers having failed in the global financial crisis, and tighter bank lending criteria making it harder for new entrants.

“What you have is a sector where there are secular trends driving demand, which gives us comfort and visibility on demand side, regardless of whether we have one or two quarters of negative GDP growth or not. And we also have good visibility on the supply side, because it takes time to bring on any new supply,” Cloete says.

“The higher interest rate environment has also made new development unfeasible for many, which gives existing landlords pricing power.”